Here is an extract from Hazel Blears’ speech this morning at Policy Exchange:

We need a sustained challenge to the Al-Qaida narrative, taken up by moderate Muslims and others, in a variety of forms. But it is not as simple as a logical Socratic debate. We make a grave error if we suppose that we will win simply by force of argument with Al-Qaida or other groups which support terrorism. You cannot conduct a negotiation with groups without hierarchical structures, or a set of negotiable demands based on political or territorial outcomes. In this key regard, our approach can not be the same as in the Northern Ireland Peace Process. You can’t win political arguments with the leaders of groups who tell lies as part of their strategy, who change the goal-posts, who spread misinformation, who intimidate and terrorise their opponents, and who believe in the destruction of the very democratic process of debate and deliberation you seek to deploy.

But whilst the Government cannot negotiate with Al-Qaida, or other supporters of terrorism, there is a much broader group of people, susceptible to the Al-Qaida narrative, who we must engage with. We cannot leave the field clear.

So we have to strike the right balance: being clear and confident in our arguments, but we must understand that to share certain platforms or attend certain conferences merely gives credibility and legitimacy to groups who do not warrant it.

That brings me to the Government’s strategy for engagement with different Muslim groups.

As a minister dealing with this every day, I can tell you there is no easy answer to the questions of when, who and how to engage with different groups. When my predecessor Ruth Kelly became Secretary of State, she made it clear that the Government would not do business with any groups who weren’t serious about standing up to violence and upholding shared values, and that has been our approach ever since.

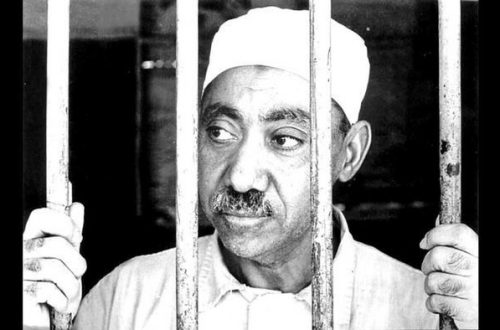

Take the Islam Expo at the weekend. I was clear that because of the views of some of the organisers, and because of the nature of some of the exhibitors, this was an event that no Minister should attend. Organisers like Anas Altikriti, who believes in boycotting Holocaust Memorial Day. Or speakers like Azzam Tamimi, who has sought to justify suicide bombing. Or exhibitors like the Government of Iran.

Not because the vast majority of Muslims at the event were not decent citizens; they were. But because the organisers were trying to influence the audience in certain directions. And by refusing to legitimise the event for these specific reasons, we would hope to isolate and expose the extremists and ensure they were not part of the event next year. Our policy is designed to change behaviour.

Our strategy rests on an assessment of firstly whether an organisation is actively condemning, and working to tackle, violent extremism; and secondly whether they defend and uphold the shared values of pluralist democracy, both in their words and their deeds.

By being clear what is acceptable and what isn’t, we aim to support the moderates and isolate the extremists. Because of this approach, there is a debate within some of these organisations. We have strengthened the hand of the moderates. I believe that this approach has helped the MCB to take the welcome step of attending Holocaust Memorial Day – a small but significant step in the right direction. We have enabled new voices to be heard, and brought new people to the table.

The Government’s process for engagement is not static, and needs continual assessment. I will redouble my efforts to make sure the engagement strategy is understand and applied across government, so that every minister knows when to accept invitations, and when to refuse, with clear criteria. And when it is appropriate for civil servants to meet with certain groups and individuals, and when it is not. This is a dynamic process: if organisations genuinely shift their positions, we can reconsider our engagement with them.

I welcome the scrutiny from outside on our engagement, especially when it comes to our funding of local groups and programmes, because we are dealing with public money. As politicians, we have no margin of error. We take every step to minimise the risk. Of course I recognise that if a single penny was to be subverted to a group or individual which opposes our aims there would be anger amongst the public, and quite right too. By the same token, outside scrutiny must be rooted in evidence and facts, not a desire to make headlines.

Nationally we need a clearer understanding of the groups we are funding through better on-the-ground intelligence (including a better relationship with local MPs and councillors who know what is going on), and we to rigorously apply the criteria to guide who we fund, for what purpose, and what we want for our money.

It is also incumbent on local authorities to maintain robust arrangements to make sure the money is focussed on projects which will make a difference, and money does not fall into the wrong hands. Recent guidance to local partnerships made it clear that local authorities must discuss funding proposals with the police, and monitor and audit the schemes.